The United States has weathered two recessions in the last decade, and the financial turmoil has taken its toll on the economic well-being of many Minnesotans. Between 2000 and 2010, poverty increased in Minnesota, median household income stagnated, and more residents went without health insurance as employer-sponsored health care declined.

The pain has not been equally spread, hitting communities of color particularly hard. In Minnesota and the rest of the country, communities of color have faced a pattern of institutional and structural barriers to opportunities – barriers that are both historical and ongoing. In 2010, for instance, blacks in Minneapolis faced a 21 percent unemployment rate, more than triple the rate for whites.[1] People of color are a growing part of the state’s population, and failure to address underlying causes of such significant disparities puts Minnesota’s prosperity at risk.

For the state to reverse these trends over the long term, Minnesota must build an economy that works for everyone. That means improving access to education and training, particularly in communities of color. And it means ensuring that work supports are available to fill in the gaps for workers who cannot find jobs that pay enough to support their families.

Poverty on the Rise in Minnesota

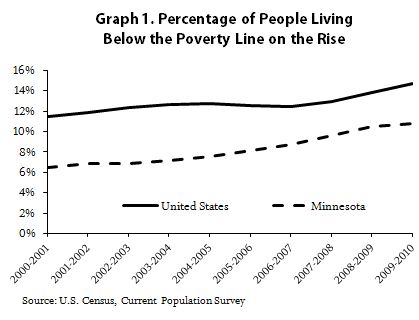

Poverty rates among some communities of color in Minnesota are higher than the national average Over the last decade, the percentage of Minnesotans living in poverty has risen significantly. By 2010, nearly one out of every nine Minnesotans was living below the poverty line ($22,113 for a family of four with two children), according to the U.S. Census Bureau.[2] The number of Minnesotans struggling to live on even fewer resources is also growing. By 2010, roughly one out of every 20 Minnesotans was living at or below 50 percent of the poverty threshold.

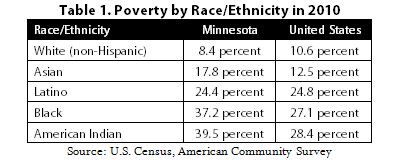

Minnesota’s overall level of poverty continues to remain below the national average. The statewide figure, however, obscures the fact that poverty is much more prevalent in communities of color. In 2010, 24 percent of Latinos, 37 percent of blacks and 40 percent of American Indians were living in poverty, compared to eight percent of white Minnesotans. And while poverty levels among Minnesota’s white population are below the national average, many communities of color in Minnesota experience levels of poverty that far exceed the national average for their counterparts.

These distressing disparities are even more evident among Minnesota’s children. For example, overall child poverty in Minnesota rose to 15 percent in 2010, a statistically significant increase from pre-recession levels. However, the poverty rate was a staggering 46 percent among black children. Research shows that living in poverty, particularly at an early age, can have a long-term detrimental impact on a child’s economic well-being. However, investments in education, including early childhood education, can help improve their futures.

The poverty threshold fails to adequately capture the true cost to make ends meet. The poverty measure was developed in the mid-1960s, and assumes a family can live on an income three times the estimated cost of a basic food budget. This outdated measure fails to recognize that food is now a smaller element of a family budget. It ignores the rising costs of other modern-day essentials such as clothing, housing, medical bills and child care. The U.S. Census has acknowledged that the official poverty threshold is “intended for use as a statistical yardstick, not as a complete description of what people and families need to live.”

Researchers often look at the percentage of people living at twice the poverty line to more accurately measure the number of families falling short of a basic standard of living. In 2010, one out of four Minnesotans was living on an income below 200 percent of the official poverty line, or $44,628 for a family of four.

Another alternative measure is the basic needs budget, developed by Minnesota’s JOBS NOW Coalition, which measures the actual cost of purchasing essentials like food, housing, health care, clothing, transportation and child care. In 2009, a Minnesota family of four with one parent working needed to earn about $36,444 to support their basic needs. However, these dollars don’t stretch far – housing costs alone eat up one-third of that budget.[3]

Median Household Income Continues to Slide

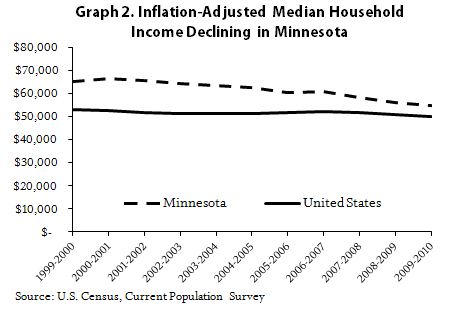

During the most recent recession, unemployment in Minnesota soared to levels we haven’t seen since the 1980s, leaving many families struggling to find suitable work. Those fortunate enough to be employed have experienced slow growth in their wages. So it’s no surprise that there has been a gradual decline in the state’s median household income. Median household income is the mid-point of household income in the state, with half of the state’s households making more and half making less. Although Minnesota’s median household income ($54,785 in 2010) remains above the national average of $50,022, it has been declining over the last decade. Between 1999-2000 and 2009-2010, the state’s median household income fell by $10,000, after adjusting for inflation.

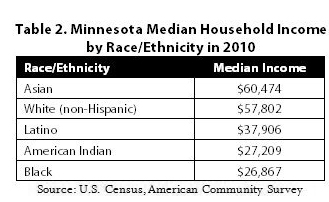

Once again, there are significant disparities within the state. In 2010, the median household income for black and American Indian households was around half of the statewide median household income for whites.

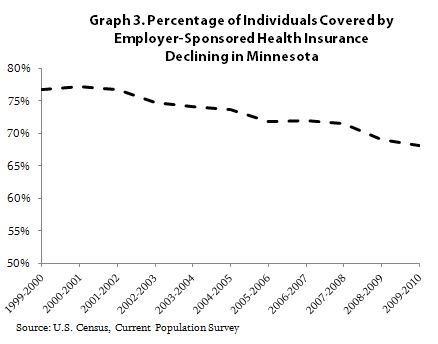

Health Insurance Coverage Declines

Public health insurance offers a safety net for many Minnesotans A third, and related, sign of Minnesota’s economic struggles is the growth in the number of people under age 65 without health insurance. The share of Minnesotans without health coverage has increased from eight percent to 10 percent over the course of the decade. That translates to approximately 100,000 more uninsured people, or roughly the population of Rochester. This trend is largely the result of declining levels of employer-sponsored health insurance. People are increasingly finding coverage through Medicaid (known as Medical Assistance in Minnesota) or other public health insurance, or they are going without insurance.

Although the decline in employer-sponsored health insurance has occurred at all income levels, it has been particularly dramatic among those living at or below 200 percent of poverty. As a result, there has been a growing number of Minnesotans both living in poverty and without health insurance. That reality impacts everyone: these low-income individuals are often unable to afford preventive care, leading them to rely more heavily on emergency room services at a higher cost for the entire health care system.

Building an Economy that Works for Everyone

The world is changing and Minnesota needs to adapt so we can prosper in the future. But we face serious challenges. As poverty increases in Minnesota, more and more families are struggling to pay for food, housing, clothing and transportation. And the growth in the number of uninsured individuals means more people without access to affordable and adequate health care. Communities cannot thrive when so many are unable to meet their basic needs.

The state faces another challenge. Our highly educated workforce helped Minnesota’s economy recover more quickly from the most recent recession than the national economy has. But our future economic growth is far from secure. By 2018, Minnesota’s employers are expected to require one of the most highly educated workforces in the nation, with 70 percent of our jobs calling for some education beyond high school.[4] Today, however, only 46 percent of the state’s working-age population (25-64) has a post-secondary degree.[5] Recent state budget cuts have fallen heavily on higher education and job training programs, reducing the likelihood Minnesotans will be prepared to fill the highly skilled jobs of the future.

Minnesota’s economic health depends on creating the workforce of the future. We know that smart public investments are an important part of the solution, including support for the state’s early childhood, K-12 and higher education systems. Education and training opportunities are of particular importance for communities of color, who historically have faced barriers to accessing education, quality jobs and decent wages. And since the state’s population is becoming increasingly diverse, Minnesota’s prosperity will depend more and more on the educational success of people of color.

If we hope to reduce poverty and overcome persistent economic disparities in our state, we will also need to maintain adequate work supports to help fill in the gap between the wages people can earn and the resources they need to keep their families afloat. This includes helping families access the food, housing, health insurance, transportation and child care they need to create a safe and stable environment.

We need to build an economy that works for all. And that means Minnesota should make public investments that will help us develop the quality jobs and strong communities we want in the future.